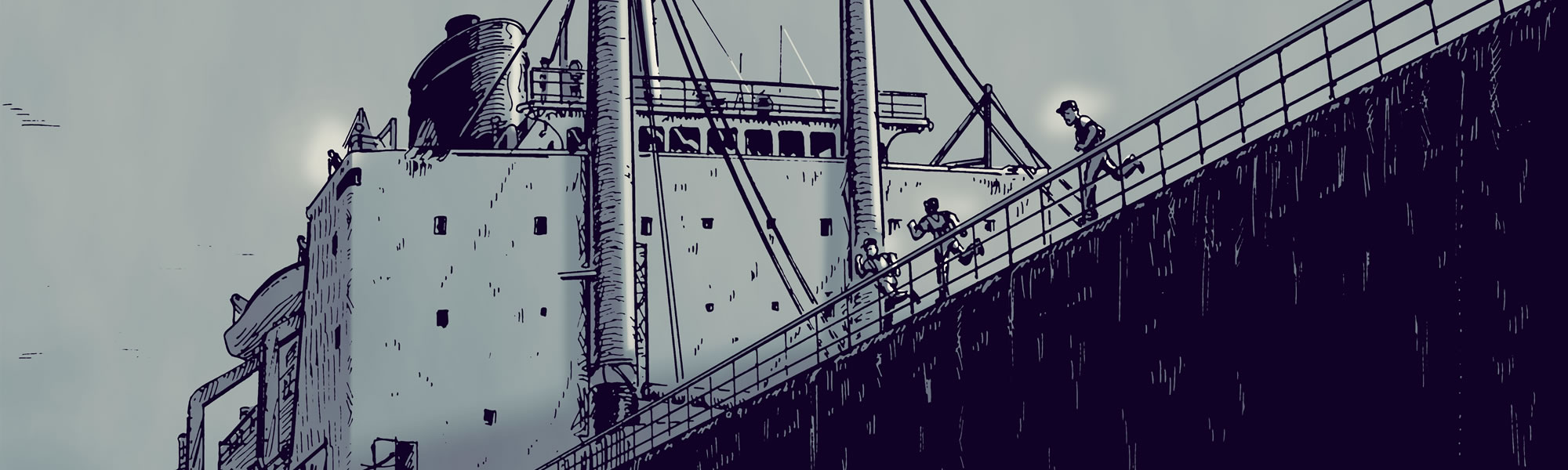

Capt. Tolley is a Columbia River Bar Pilot who has circled the globe many times in 24 years at sea—in the Navy under combat, as a merchant mariner on tramp steamers, even as master of a wooden schooner caught in a storm with four feet of water in the bilge.

Tolley has many great sea stories. Some of the most intriguing and adventurous are shared here. Through them all, he says, he has been guided by seat-of-the-pants training, beginning at MMA, and a willingness to fight for what’s right and “think outside the box…”

It’s May 29, 2018,

and I’m piloting an outbound, 738-foot Panamax bulk carrier loaded with 60,000 tons of soybeans, approaching the Columbia River Bar. The channel is dredged to 43 feet, the ship draws 43 feet and we have 3 feet of water under her keel.

We’re coming up, full-ahead, sea speed, at Buoy 21 when there’s a sudden quiet instead of the rumble of the engine. I look down and see we’re at 40, then 35 RPMs.

I ask the captain, “You gonna call the chief? What’s going on?”

“Captain, we need to know now when we’re going to have RPMs back up.”

He calls the chief and learns they’ve lost jacket water cooling, and so the engine is overheating.

“OK, Captain.” I stay as calm and collected as I can muster. “Here’s what we’re going to do…”

We’re very, very heavy, very deep, and we’ve got a lot of current. If we drop and lose an anchor, we’ve got a big problem. I order the starboard anchor lowered a half a shackle into the water and make her ready for letting go, hoping to anchor just outside the channel in deeper water, trying to slow down the vessel using her rudder and dragging the screw through the water.

We’re very, very heavy, very deep, and we have a lot of current. If we drop and lose an anchor, we’ve got a big problem.

“Captain, let go three shackles…the anchor should be bouncing off the bottom…now let’s veer out to 10 shackles.” The bow rounds up into the current, but we drag across the channel with the ebb current at 2.5 knots toward the jetty at Buoy 11.

And then I let go the port anchor, which I am hesitant to do because it could tangle with the starboard anchor.

Now we’re down to 1.7 knots but still heading toward the jetty, the buoy, and a 23-foot shoal spot just off the port beam. So, we use the rudder, the anchors, the wind and those 30-40 RPMs to our best advantage to not take out or tangle the buoy with the screw while being mindful of the current as well.

We use everything we’ve got and make our way clear of the buoy, ease off the RPMs, and come to a stop with the anchors holding, and tugs arriving, almost 5 hours after losing steerage.

You know, you go through rough times in your life, but they happen for a reason. All the training I did at MMA and in the Navy, maybe that saved my butt—more than once!

Right Place, Right Time

Before MMA, I attended the University of Utah, and I joked that I was pre-med, pre-law, and pre-school! I never would have graduated.

But then I came to Castine. I went on the freshmen training cruise as a deckie, and everything just clicked and fell into place for me. The structure of the learning was what I needed, and I was determined to be a mariner from then on. It was like I was supposed to be there.

That’s the way my life has unfolded, although I haven’t always been able to see it at the time.

After MMA I took a commission in the Navy, went to the USS Rushmore (LSD-47) dock landing ship, became a navigator, boat wave commander, and early on, won the Ship Handler of the Year Award for the Pacific fleet. It all turned out to be quite an adventure. A couple of experiences stand out.

War Time

In 1994, when I was first attached to the ship, I led troops, mostly Marines, ashore for the evacuation of the U.S. Liaison office in Mogadishu, Somalia. In August of the same year, we were part of an Amphibious Readiness Group off the coast of Kuwait and received orders to hold the line and deter Saddam Hussein’s invasion farther into the country.

One of the landing craft I used to lead troops ashore caught fire and I had to beach it. I left the boat and the crew safely there, and with a fellow crew member, walked most of the day. It was surreal.

We headed for another landing craft farther away. Things all around had been shot up from the fighting, and jeez, you didn’t know if there were enemy forces in the area.

Eventually, I made it back to the ship, snagged another landing craft, got my crew and towed the boat back to the ship. It all seems now like something only a couple of crazy 20-something-year-olds would do.

In addition to being navigator on the Rushmore, I was the helicopter control officer, in charge of all flight ops, which gave me the opportunity to work with and observe Navy SEAL teams on the ship. Everything they do is extreme…fire practice every single morning, fast roping and swimming, then catching a ladder, climbing up into a helo. I had no idea about SEALs at the time, but the experience helped me think outside the box when I became a merchant captain.

Pirates Come Calling

After the Navy, I needed a change and worked as master of a couple of New England schooners and did boat deliveries before getting married. Then I had to get a real job.

I worked as Third Mate and eventually Master/ Captain for Sealift, Inc., delivering food aid all over the world aboard tramp steamers. It was old-time tramp steaming, splicing wire rope for rigging, speaking Swahili in Kenya and Wolof in Senegal…it was just amazing. I’d been inspired by one of my MMA professors, Capt. Al Brown, who had done the things, tramped all around Africa.

November 2, 2009, aboard the bulk carrier MV Harriette, I had taken departure from Mombasa, Kenya, and was bound for Mumbai. We were on an easterly course late in the morning when I got a call from the third mate: “Captain, we have inbound boats.”

A helipcopter captured this photo of one of several boats with Somali pirates who attempted to overtake Tolley’s ship in 2009.

I ran to the bridge, looked out, and saw two inbound skiffs (Somali pirates) broad on my port bow. I ordered the helmsman, “Hand steer, left 20. Get down on your knees. They’re going to try to shoot out the windows.”

I was thinking, You can’t be intimidated. You’ve got to take the fight right to them.

We turned toward the skiffs, sounded the ship’s whistle and were on a closure rate of 35-40 knots. We sounded the general alarm, put out a Mayday call and another to the International Maritime Bureau. We were 364 nautical miles east of Mombasa. They were out there, just waiting for us.

My adrenaline started pumping. I had a gangway security team, but they were unarmed, except for a couple of paintball guns. We were taking a butter knife to a gun fight.

We were taking a butter knife to a gun fight.

Yes, we had the ship’s hoses run out on the bridge wings and on deck, but I didn’t think that was going to do much. So as they came upon us, I turned hard to port, and, boom, my timing was just right; we nailed the first boat, which then was sent dragging down along the side of the ship.

The second boat overshot the bow to starboard as I was turning. He rounded back up but hit our wake, which threw them into the air and either swamped the skiff or caused engine problems so that they couldn’t keep up with us.

The first skiff gained steerage, approaching port midship with a wide hooked ladder in the air. I ran out on the port bridge wing, screaming and yelling. Just as they were about to connect, I gave the command for hard to starboard. It created just enough of a wedge of water to drive them away and miss connecting. They tried again. The chief put in maximum RPMs, and they slipped aft but came chasing back after us.

I grabbed one of the paintball guns and leaned out over the bridge wing with it showing, yelling every threat I could think of. One of them stood up and pointed an RPG (rocket-propelled grenade launcher) at me. I thought, “Oh, God…”

They could have maybe hit me or put it into the side, but I believe at that angle it was too tight, too steep. Out of frustration they started firing off their AK-47s. They shot up the port lifeboat and a few holes near me. But I kept leaning over to watch them and calling maneuvering commands to the helmsman. We began to slip away, and they gave up and turned away.

We made our way on to Mumbai, but there would be another bout with pirates, four years later off the West Africa coast.

Great Balls of Fire

On July 18, 2013, I was captain of the MV Liberty Grace, a handymax bulk carrier, and we were off Lome, Togo. At 1:54 in the morning, I received a call from the second mate from the bridge: “Pirates on board. Pirates on board.”

We had strung razor wire around the perimeter of the deck, and they were in the process of cutting through it.

This time I was better prepared. We had rigged up 4-foot sections of pipe with end caps and stuffed them with contents from our parachute rocket flares, ball bearings and anything else we thought might work. There were three skiffs full of men around the ship.

We put on welders gloves, took aim and fired one off through the pirates down into one of the skiffs. There was a sonic blast, burst of flames. It rained into the skiff, and the pirates at the rail went into the water. Men in the skiff went overboard, and then all three skiffs circled in the darkness trying to recover their men. We couldn’t see what was happening, but we pulled away. It was crazy.

They ended up taking another ship after the attempt on us.

Mediterranean Rescue

Of all my time at sea, the most significant event for me occurred on November 17-18, 2014, aboard the MV Liberty Grace in the Mediterranean.

We were sailing from Bahrain back to the States. I had just left the bridge for breakfast when the mate called, “Captain, we’ve been diverted by the Italian Navy. There’s a fishing trawler with refugees.”

It was 12 miles away, and we went right to them. As we approached the blue-and-white 78-foot trawler, I could see water coming over the side from the bilge pumps, and the engine was clearly not working, probably due to a lack of fuel. There were 241 Syrian refugees crammed aboard.

We passed a sea painter down and made them fast. I was able to control the ship so that we could safely tow the trawler and lower our gangway down onto its deck. Thankfully, conditions were perfect. Any kind of weather, and we would’ve had to use the pilot ladder, and I don’t know how we would have done it.

Tolley and crew rescued 241 Syrian refugees aboard a disabled trawler in the Mediterranean. “They looked like images from Auschwitz…”

For more than two hours, they came aboard—men, women, children, babies, people who had been shot. They had been suffering various sicknesses, wounds, lack of food and water. As they slowly lined the deck of the Grace, they looked like images from photos of those on the train tracks of Auschwitz.

The first thing they said was, “Water, water, water, water…”

The next thing was, “Shampoo, shampoo, shampoo…” They wanted to restore their dignity.

They’d left their country primarily from two towns, Aleppo and Homs, where they had suffered unbelievable oppression and been bombed with chemical weapons. As we got them settled on the ship, you could see them starting to relax, and all these children had smiles on their faces.

But they soon became worried: “What’s next? Will we be sent back to Syria?”

The leaders among them wanted certain things, and I made that happen. They wanted the UN High Commissioner for Refugees and the Red Cross there. I put the request in, and they were answered affirmatively.

They lucked out because they were granted asylum. Today, they’re in Sweden, France, Germany, and all across Europe.

They were amazing people. Many had led careers as doctors, lawyers, engineers, and journalists, but they left with only backpacks, some water and a change of clothes. They left everything behind and suffered through so much. It was an honor and privilege to serve them, and I’ll never forget it.

My whole crew jumped to the tasks. It took all of us and was continuous.

You’ve got your moral compass and you’ve got the law of the sea, and you have to do what’s right.

To be honest, the ship’s owners weren’t that pleased by our involvement. But I would still do the same thing. You’ve got your moral compass and you’ve got the law of the sea, and you have to do what’s right, regardless.

Meant to Be

One of my inspirations has been Capt. Deborah Dempsey ’76, the first female to graduate from MMA, of course, and the “first” at many other things in her career, including becoming a Columbia River Bar Pilot. In 2013, I had interviewed for a job with the Oregon Pilots, as she had done, but I didn’t make it.

I interviewed again in 2015. This was after the second pirate attack, the Syrian refugee rescue and many more miles at sea, and I stood before the Board once more. I think these experiences put me over the top.

Capt. Tolley with representatives of the rescued Syrian refugees. “It was something I’ll never forget,” he says.

Leadership has always been a core value to me. Its importance was instilled in me right from the beginning at MMA.

A leader is someone who will jump in and fight alongside his or her crew and get the job done. You have to inspire and lead people by being an example to them, but you also have to serve and take care of your crew, look after them.

When I look back on life, I believe I’ve been led by my faith, and offered opportunities where I had to connect the dots and make the right decisions.

So far, so good. I am humbled to have been so fortunate.█

Art: Ted Slampyak; Photos: courtesy of Michael Tolley

Post Comment

Congratulations captain Micheal Tolley.

What a great life story.

Proud to be your brother.

Comments are moderated and will be reviewed prior to posting online. Please be aware that when you submit a comment, you agree to the following rules:

Maine Maritime Academy reserves the right to delete any comment that does not comply with these guidelines and is not responsible or liable in any way for comments posted by its users. If you have a message for the editor, please email mariner@mma.edu.

Features

View All >Read More

Read More