(Orville Schell is a Harvard student studying in the Far East.)

ANTOI, Viet Nam — On a remote island off the tip of southern Viet Nam, a Navy lieutenant from Rockland, Me, lives an almost squalid life among Vietnamese who man junks in patrols along the swampy, treacherous delta coastline of the Ca Mau peninsula.

The junks stop and search craft that might be secretly bringing arms and supplies to Communist guerrillas in the area.

In his sea-sprayed New England twang, Lt. Wesley Hoch, barefoot and dressed in a baggy black tunic that is the uniform of the junkmen, sounds peculiarly out of place standing at the door of the structure that is his district headquarters. Before him, out in the harbor beyond the barbed wire, is part of his fleet — a motley collection of junks.

Hoch is as much at home with the Vietnamese as if he were born in one of the small grass roof shacks that make up the village out of which he operates.

He has a rare rapport with the junkmen with whom he works. They, in turn, are devoted to him.

For Dai Wei Hoch (their name for him) is one of them — 24 hours a day.

He wants no escape to separate quarters, clean rest rooms, Western food, military clubs, and air conditioned rooms when 5 o’clock rolls around.

Unlike so many other American advisers in Viet Nam, Hoch lives, sleeps, eats, and fights 24 hours a day, every day, with his junkmen. He refuses to accept any privilege for himself that he cannot give his men. He says he hates to see stuff sit in Saigon warehouses rotting when his men are cold at night, wet during the day, undernourished, and manning junks that are short of arms.

He has been known, when making one of his rare trips to Saigon, to drive a borrowed truck up to a warehouse during lunch hour and just start loading things into it — as if he owned the place. In this way he brings precious things to people fighting a war with empty stomachs and hardly a shirt on their backs.

The first thing he did when he arrived at Antoi, a small fishing village on the island of Pho Quoc, was to rip the sign off his door that said Cam Vao (do not enter). He runs as austere mobile force that fights the Viet Cong guerrillas on their own terms. He does not want a large-scale, super-organized force that would sacrifice the comradeship of his smaller group of men who can live off the land and trust one another.

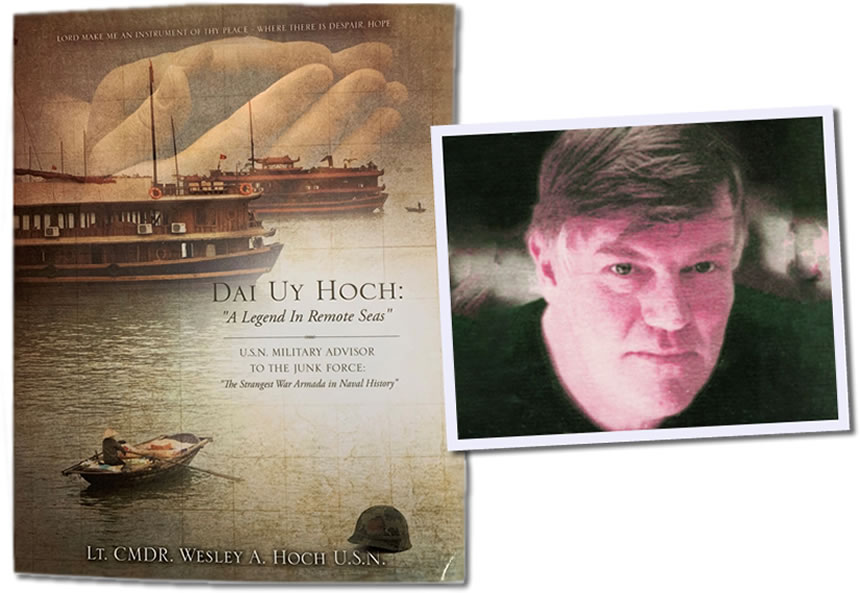

A later photo of Hoch and his book titled “Dai Uy Hoch: A Legend In Remote Seas,” a manuscript about his time in Vietnam.

In the life of LT Wesley Hoch — in a war most Americans forget — there is no time for the beer runs and the endless movies that keep most other American advisers entertained at night. There is no hot water heater that will be transported at the expense of something more necessary to the people or the war.

He says that one has to give everything or nothing at all, or one will fail. This is the creed he lives by.

The result: His men respect him. And the enemy has placed a 500,000 piastre bounty (about $7000) on his head.

When not on patrol, Hoch lives in the sparse remains of a garrison building the French vacated. Two rickety double-decker bunks junkmen share with him (depending on who gets tired first), a gas ice box filled with medicine and a few squash or melons are the only furnishings. The kitchen consists of a tub of water.

On the wall, several .45 automatics and a rack of M1 rifles and clips complete the scene. The “Antoi Hilton,” as Hoch calls his quarters, sits close to the beach looking to a number of tropical islands in the distance. Behind his small compound sits the village of Antoi.

And behind the village, a hill rises. Almost every other night the Viet Cong muster on the hill after dark and launch an attack. During the day the Viet Cong are too wary to attack.

When at the base he does anything from writing reports to requesting more equipment to distributing whatever he has managed to beg, borrow, or otherwise appropriate from what he calls the “air conditioned empire” of Saigon. Other days are spent trying to get damaged junks back into working order.

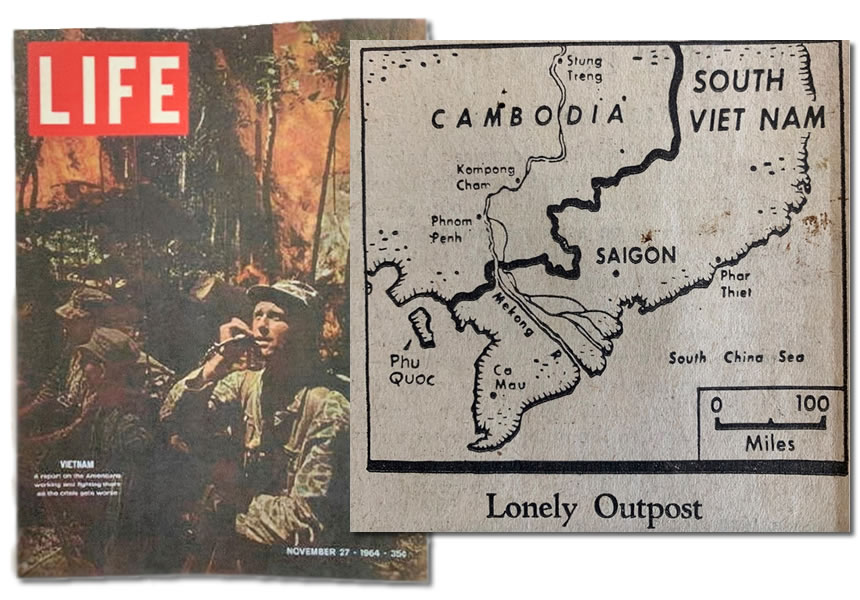

The cover of LIFE magazine from November 27, 1964 which includes an article about the Black Pajama Navy and how “LT Lovdal’s job at Phu Quoc has been made easier because of the pioneer work of his predecessor, LCDR Wesley Hoch of Rockland, ME.

For a week, Hoch will put to sea in one of his patrol junks to check posts up and down the coast. He takes no special rations for himself. Instead, he brings paper, pencils, books, shoes, medical supplies, and food to the people who live in the forgotten backwaters of this embattled nation.

If the men catch no fish on their long sea journeys, he goes hungry with them; if the mosquitoes are biting, he is fair game. If the area is dangerous, he shares in the danger.

He is a strange mixture of soldier, sailor, dentist, mechanic, linguist (he speaks a fractured Vietnamese), doctor, and teacher. He claims to have no special proficiency in any of these things, but maintains that anything that one can do as an amateur is better than sitting around doing nothing at all.

Most of the small coastal villages to which he goes are dirty, poverty-stricken areas accessible only by sea. What is more, they are infested with the enemy.

Hoch runs his junk force in a way that is seldom found in the impersonality and coldness of the war here in Viet Nam. He is a man who has been presented the job of building an effective junk patrol force for the Navy. He has done this, but he has not stopped there.

Hoch has a private theory, that if one will only sacrifice a little more, share a little more the dirty work with the people about whom the war is being fought — then it will be won a lot sooner.

To him, this does not mean going on a dangerous mission and then returning with relief to the comfort of Saigon, leaving the men who were being advised behind in the mud.

The war, for him, is not like holding your nose for a brief moment through a bad smell.

He is in it the whole time and asks no exceptions because he is American.

This rare dedication has one visible side effect among the sincere and grateful Vietnamese: To them, Dai Wei Hoch already is a living legend.█

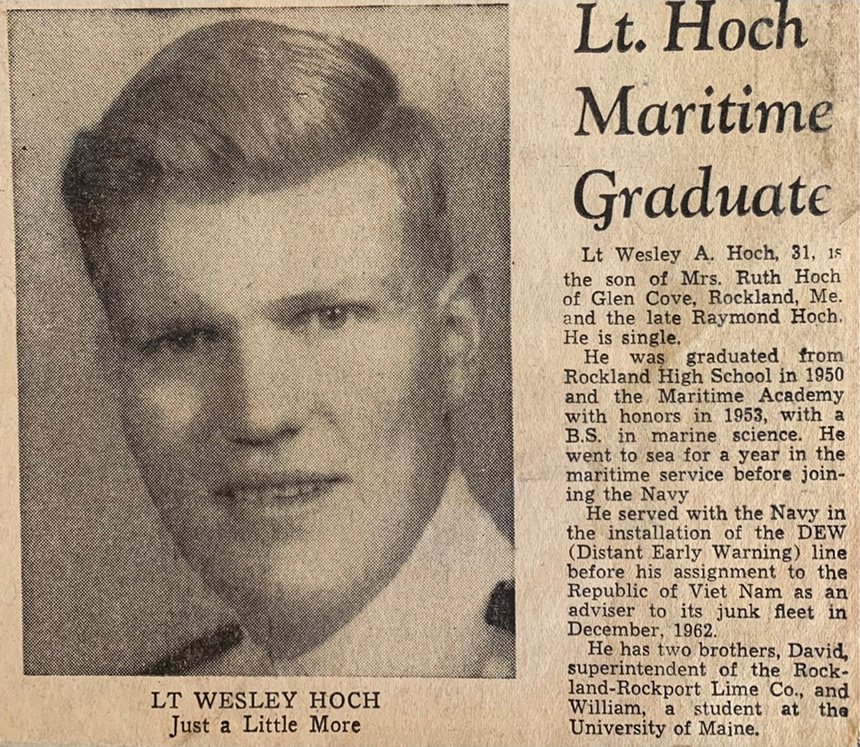

I happened across this article from the Boston Sunday Globe, dated October 20, 1963, while organizing boxes of alumni files, documents, clippings, slides, and correspondence, among other things. The treasures were numerous, but this made me pause… Wesley Hoch, class of 1954, in the Boston Sunday Globe?

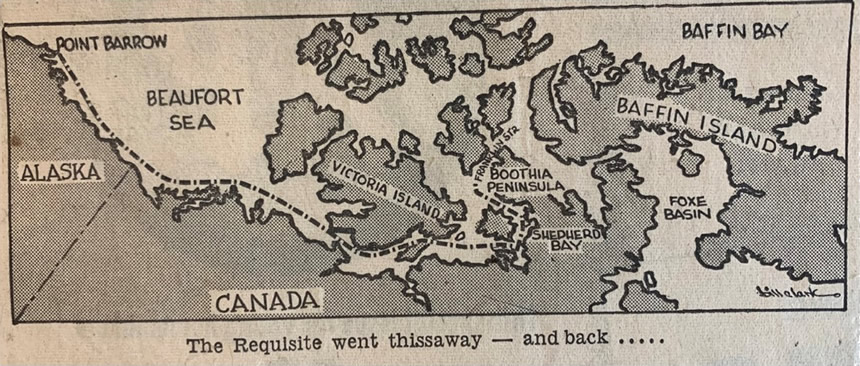

The research began… more newspaper clippings: a Portland Press Herald article (April 26, 1957) following Ensign Hoch in “sort of a resumption of the search for the Northwest Passage” aboard the Requisite, a U.S. geodetic survey ship, following two ice breakers from west to east for 1,800 miles, only to be stopped by ice 50 miles from their destination; a LIFE magazine article (November 27, 1964) about the Black Pajama Navy and how “LT Lovdal’s job at Phu Quoc has been made easier because of the pioneer work of his predecessor, LCDR Wesley Hoch of Rockland, ME… ‘I heard a lot about Hoch and the wonders he performed with the scruffy little group of junks. The VC respected him so much they put the flattering price of 500,000 piasters (about $7,000) on his head…’”; and a book titled “Dai Uy Hoch: A Legend In Remote Seas,” a manuscript about his time in Vietnam that sat for over 40 years, published by his brother David after Wesley’s unexpected death December 23, 2004 at age 72.

His accomplishments and accolades are many, several documented in his book and mentioned in his obituary (see Eight Bells at mainemaritime.edu/alumni). To add to his honors, Wesley Hoch was the first to be named Maine Maritime Academy Outstanding Alumnus (1964). He is also on the MMA Wall of Honor for attaining “high levels of leadership within their chosen fields. By force of effort and ability, they have attained distinguished positions of responsibility. Their accomplishments have served society and brought credit to the Academy.”

Orville Schell, the author of the article, is a long-time China observer, author, journalist, and former dean and professor at the University of California, Berkeley. He has been a contributor on China for PBS, NBC, and CBS, where a 60 Minutes program of his won an Emmy.

I hope you find this article as interesting as I do, and I highly recommend reading “Dui Uy Hoch: A Legend In Remote Seas.”

Post Comment

Comments are moderated and will be reviewed prior to posting online. Please be aware that when you submit a comment, you agree to the following rules:

Maine Maritime Academy reserves the right to delete any comment that does not comply with these guidelines and is not responsible or liable in any way for comments posted by its users. If you have a message for the editor, please email mariner@mma.edu.

Features

View All >Read More

Read More

Castine, Maine 04420All Rights Reserved © 2026

Privacy Policy & Terms

Web issue? Contact Webmaster