The economy of Maine is diversifying and creating opportunities in offshore renewable energy, expansion of fisheries, and growth in aquaculture. In addition, coastal communities and businesses will need to assess and adapt to environmental change. A deeper understanding of coastal and ocean ecology is critical to the success of these economic opportunities. To sustain Maine’s marine industries, we need to know more about how these systems are driven by marine species at the bottom of the food chain, the ecological and economic vulnerability created by introduced and non-native species, and potential shifts in biological diversity. Biological monitoring is a basic tool to understanding system change. Maine’s workforce needs people capable of monitoring the environment to safeguard the natural resources essential to Maine’s economy.

MMA’s Corning School of Ocean Studies newest program, Coastal and Marine Environmental Science, is using two important new technologies to monitor aquatic ecosystems, thanks to funds from the Maine Economic Improvement Fund (see story at bottom of page). Students in the program are being trained as marine environmental scientists who can work across academia, conservation, resource management, business, and public policy.

Doctors Steven Baer, LeAnn Whitney, and Kerry Whittaker are professors in the Corning School of Ocean Studies. Together, they wrote the grant request to integrate two new technologies into MMA’s ocean studies curriculum that make it possible to collect more and better information about the ocean.

One of these tools, the Yokogawa FlowCam, uses imaging technology combined with software to quickly capture and analyze large amounts of data about phytoplankton. Phytoplankton are single-celled organisms that float in the light-lit surface ocean. They contain chlorophyll, take up carbon dioxide, use sunlight to make carbohydrates, and release oxygen, just like land plants. The FlowCam was invented in Maine and is manufactured and serviced here as well. It uses laser detection and a powerful lens to capture images of plankton (0.01 to 1 millimeter in size). The FlowCam can analyze up to 10,000 plankton cells (or particles) per minute from a sample of seawater. This radically improves monitoring and analyzing phytoplankton communities in the marine environment. The software identifies species and estimates the population of phytoplankton, along with a host of other characteristics.

The three professors have all worked with this technology in labs and in oceans from the Arctic to the Antarctic. “The FlowCam is just objectively cool,” says Dr. Whittaker. “To see what is in a sample of water is just amazing. There is a ton of data and opportunities for analysis.” Freshman Lily Verrill is in “Introduction to Oceanography and Environmental Science,” taught by Drs. Whitney and Whittaker, and agrees. Talking about the FlowCam, Lily said, “The FlowCam is astounding, and it’s really cool how it can group pictures by similarity to a known dataset or even to another picture in the sample! It makes counting and identifying phytoplankton much faster and can capture far better images of microscopic particles and organisms than I can. And it’s not incomprehensible to operate.”

“Maine Maritime Academy is all about active learning. The equipment we have in the lab is not for us—it’s for the students. This equipment is out on the lab bench; it’s available for students to use. This makes MMA unique. We are providing students opportunities that make them valuable in the wider world.”

The other tool new to MMA is a quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction (qPCR) instrument manufactured by BioRad. It can be used to detect and measure the abundance of organisms by analyzing DNA in the environment. This DNA comes from cellular material that was shed by organisms (via skin, secretions, etc.). A sample of sea water can be analyzed with qPCR to learn what organisms have been in the area. PCR uses short synthetic DNA fragments called primers to select a segment of the genome to be amplified, and then multiple rounds of DNA synthesis to amplify that segment. (You may have read about PCR in descriptions of how vaccines are produced quickly and in large volume.) For the qPCR instrument to work, it needs to be prepared with species-specific (or gene-specific) “primers” that will then seek out the DNA scientists are interested in finding in an environmental sample. Once the primers find the complementary DNA in the sample, that DNA is amplified, and the instrument can quantify the abundance of the gene. For instance, it might show that a particular species of salmon swam through the area recently. This is important for the early detection of invasive species as well as for detecting rare species.

MMA graduates trained in these technologies will contribute to Maine in important ways. They will bolster Maine’s environmental science workforce with skills needed for Maine’s economy to grow. Their work will foster coastal Maine research collaborations and improve the technological capacity for important biological monitoring that will support coastal and marine economies.

“This is workforce development,” Dr. Whitney emphasizes. “We are getting students trained on how to use this technology and how to apply the knowledge they gain. They are ready to do this work when they graduate. We worked with stakeholders as we were developing the grant request. We asked them how they’d like to see this equipment used. What could be helpful to them? We got support from at least half a dozen agencies confirming that students with these skills would be beneficial to their work. This project is unique because we aren’t just focusing on a research project or idea. We acquired the equipment and are training our students for jobs that our stakeholders have available.”

“I enjoy learning by doing,” Dr. Whitney continues. “And I love giving students that same opportunity I enjoy. Maine Maritime Academy is all about active learning. The equipment we have in the lab is not for us—it’s for the students. This equipment is out on the lab bench; it’s available for students to use. This makes MMA unique. We are providing students opportunities that make them valuable in the wider world. It’s not about some professor’s research. It’s about students learning and applying that learning.”

Dr. Whittaker agrees. “We are training MMA students in this technology of environmental DNA. They monitor how the oceans are changing. They are learning how primary producers (phytoplankton) are changing. For instance, this can alert us to algal blooms. These can be harmful to humans, to shellfish, to other food sources. They can close a fishery for months.”

This monitoring and reporting are not just for scientific interest. They link directly to coastal resilience and the ability of Maine coastal economies to continue thriving. These new techniques produce more data than was previously possible. “It profoundly enhances our ability to monitor the marine environment,” says Dr. Whittaker. “Students are excited about what they are seeing and learning. They are learning genetics, but not just learning genetics as a stand-alone topic. They are using genetics as a tool to answer important ecological questions.”█

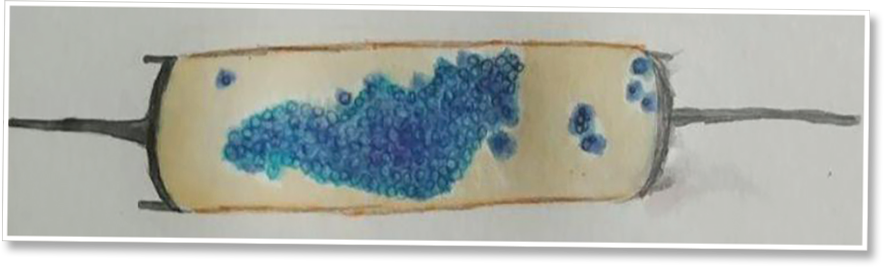

(Above) Student watercolor of Ditylum brightwelli, a species of phytoplankton. Students draw and paint organisms seen through the FlowCam to sharpen their observation and identification skills.

UMaine Small Campus Initiative Funds High-Tech Equipment

In 1997, Maine created the Maine Economic Improvement Fund (MEIF). Its purpose was to advance research at Maine’s public universities that would, in turn, improve the civic and economic life of Maine. Twelve years later, the University of Maine created the Small Campus Initiative (SCI) to provide MEIF to the five smaller University of Maine campuses (University of Maine at Machias, University of Maine at Farmington, University of Maine at Augusta, University of Maine at Fort Kent, and University of Maine at Presque Isle) and Maine Maritime Academy. The decision to include Maine Maritime Academy with the UMaine small campuses was important recognition of MMA’s value to Maine. MMA has a strong history of providing an excellent education combined with a practical focus on workforce training. It is recognized for producing graduates trained and ready to join Maine’s workforce as scientific and engineering professionals.

The SCI added the energy and talents of faculty at the smaller UMaine campuses and Maine Maritime Academy to Maine’s research sector. The emphasis was on applying new technology for economic growth and training students in those technologies. It was expected that the results would create technology jobs and build stronger relationships among Maine’s research and business sectors. The result would be increased research efforts, new technologies with licensing and commercialization potential, and creation of jobs that would be filled by a high-tech workforce developed at the participating schools.

“This program is really about building capacity for research and development in the state with a focus on primarily undergraduate institutions like MMA where field-based and experiential learning are key parts of the funded grant projects,” says Jason Charland, who serves as the program officer for the MEIF SCI program. “MMA faculty can receive grant writing training and consult with research development staff at UMaine. Inclusion of MMA faculty in the grant writing workshops has been a great new initiative of the program and also helps facilitate relationships and collaborations with colleagues at University of Maine System campuses.”

Post Comment

Comments are moderated and will be reviewed prior to posting online. Please be aware that when you submit a comment, you agree to the following rules:

Maine Maritime Academy reserves the right to delete any comment that does not comply with these guidelines and is not responsible or liable in any way for comments posted by its users. If you have a message for the editor, please email mariner@mma.edu.

Features

View All >Read More

Read More

Castine, Maine 04420All Rights Reserved © 2026

Privacy Policy & Terms

Web issue? Contact Webmaster