SHEPARD was born in Boothbay Harbor, Maine, in 1926, the fourth child of Virginia and Lorrin Shepard. Lorrin, the son of American medical missionaries, was born and raised in Turkey. Eventually, he was sent to New Jersey to live with a pair of aunts and attend high school. He then worked his way through Yale and Columbia Medical School. When Barclay was a year old, his parents decided to return to Istanbul. There his father founded the American Hospital and served as its director for 30 years.

Shepard was sent back to America when he was 12 to attend Deerfield Academy. From there he went to MMA, graduating in 1946. “I went to sea for a year as 3rd mate on an American Export Lines victory ship,” he recalled. “I dreamed of a commission in the Navy, but the war was over, and the Navy was downsizing. I decided to go to Bowdoin College and graduated in 1950.”

“What do I do now?” he wondered upon graduation. He had met Martha Loughman at Bowdoin and they had fallen in love, so they married, sailed to Turkey, and Shepard began teaching English at Robert College in Istanbul. His father was still the director of the American Hospital and Shepard found himself increasingly drawn to medicine. After three years of teaching English, his mind was made up: he wanted to become a doctor, following the path of his father and grandfather.

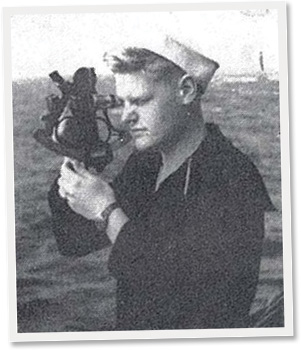

Dr. Barclay Shepard’s photos in the 1946 Trick’s End.

Barclay, Martha, and their baby Douglas sailed back to America. “I’d had a biology course at Bowdoin,” recalled Shepard, “but I needed organic and inorganic chemistry to get into medical school. I learned that Harvard offered an intensive six-week course in inorganic chemistry, and I enrolled. It just about killed me, but I made it through. I then went to Boston University for courses in organic chemistry, physics, anatomy, and histology. I applied to several medical schools and was accepted by Tufts. By then, Martha and I had three children, so I joined the Navy to help pay the bills. They paid me as an ensign until I graduated in 1958. During my senior year I was on active duty in the Navy in the Medical Corps. After graduation on June 1958, I was promoted to lieutenant and received orders to start my one-year rotating internship at the National Naval Medical Center in Bethesda, Maryland. After that I started a four-year residency in general surgery, the last year of which was in the thoracic surgery service where I assisted on the first open-heart operation at Bethesda.”

Following his residency, Shepard was assigned to the Naval Hospital in Beaufort, South Carolina. He was certified by the American Board of Surgery and became a Fellow of the American College of Surgeons. After two years at Beaufort, he applied for a residency in thoracic surgery and received orders to the Naval Hospital Long Island (St. Albans) in New York.

It was at this time that U.S. forces were heavily engaged in the Vietnam War. “I decided to volunteer for duty in that arena,” recalled Shepard. “I received orders to report to the USS Repose, one of two hospital ships operating off the coast of Vietnam. I was one of the two Navy thoracic surgeons in Vietnam. It was a long year of treating many kinds of serious battle wounds. I also successfully performed an open-heart operation on a Vietnamese soldier.”

After his one-year tour in Vietnam (1967–68), he returned to St. Albans for two years as the chief of thoracic surgery, followed by two at Bethesda. He was then assigned to the office of the Navy Surgeon General where, for nearly four years, he was the director of the Medical Facilities Planning Division. This job included working on the design and construction of several hospitals and clinics.

In 1979, Shepard retired from active duty after 22 years and moved to the Veterans Administration where his duties included monitoring the surgical departments at all VA hospitals. Shepard recalled, “It was about this time that the controversy about the defoliant Agent Orange was becoming an urgent issue. The VA was being taken to task for not connecting the dots between various health problems of Vietnam veterans and their exposure to Agent Orange. I was assigned to organize a research program to shed more light on this issue. I told them I was not familiar with this type of research, but agreed to do my best.”

Dr. Barclay Shepard’s photos in the 1946 Trick’s End.

Shepard hired an epidemiologist and a statistician who began designing studies to help answer these questions. The first challenge was to find a way to compare groups of soldiers who had been exposed to Agent Orange and those who had not. He quickly found that the Department of Defense personnel records were not very detailed about where and when troops served. Eventually, Shepard and his team were able to identify soldiers who had served in the northern part of South Vietnam who had been on the ground where Agent Orange was sprayed. They also identified the Air Force pilots who had flown the planes doing the spraying. These two groups were the most heavily exposed. At least initially, that study did not show any ill effects of Agent Orange.

Shepard’s team also designed a very large mortality study which revealed that troops who were exposed to Agent Orange had an increased risk of developing two types of cancer: non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma and soft tissue sarcoma. At the request of the VA, Congress finally passed the necessary legislation to classify these diagnoses as related to veterans’ military service. Later, additional diseases were added to the list of illnesses caused by Agent Orange.

Back on campus for Homecoming, Shepard reflected on his time at MMA in the 1940s. “It was a wonderful part of my teen years. The midshipmen came from all walks of life, but we were united by our desire to serve our country during a time of war.

“The learning was enjoyable. It was learning by doing, and that was new to me. Lt. Cmdr. Tumey took me under his wing. He taught navigation, and I loved it.”

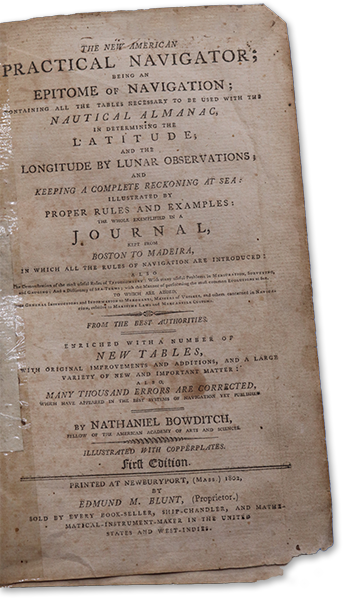

The 1946 MMA Trick’s End suggests he was not alone in his admiration for Cmdr. Tumey. The class of ’46 dedicated the yearbook to him with “respect and affection.” In the dedication, they wrote, “Mr. Tumey did not fail to infect future deck officers with his love of navigation. [With] hat turned backwards, with sextant in hand and squinting skyward; by these things may we, and countless others, remember him as our preacher with Bowditch as our bible.”

With Tumey remembered holding Bowditch in his hand like a bible, Shepard’s gift of a first edition Bowditch seems to bring the story around full circle.█

Post Comment

Comments are moderated and will be reviewed prior to posting online. Please be aware that when you submit a comment, you agree to the following rules:

Maine Maritime Academy reserves the right to delete any comment that does not comply with these guidelines and is not responsible or liable in any way for comments posted by its users. If you have a message for the editor, please email mariner@mma.edu.

Features

View All >Read More

Read More

Castine, Maine 04420All Rights Reserved © 2026

Privacy Policy & Terms

Web issue? Contact Webmaster