When Eric King ’90 explained the workings of the 363-foot ocean research vessel Falkor (too) during a Zoom call this past January, his hands came alive. He made circular motions to accompany a description of the amazing propulsion system run by Voith Schneider Propellers, whose vertical blades spin in the same direction. In describing the hangar that holds the ship’s remotely operated vehicles, or ROVs, his hands and arms attempted to articulate a large protective space in the belly of the vessel.

King became even more animated when talking about the the ship’s 2023 expeditions. The crew complement is 28 but the ship has 70 additional berths for scientists, ROV pilots, artists, media personnel, and students. In June they will be on an “octopus odyssey” to investigate the biodiversity of unprotected seamounts off Costa Rica. Later in the year they will be exploring hydrothermal vents and vertical reefs in the Galápagos. The team will also be testing the capabilities of a new technology that provides high-resolution 3-D mapping of the seafloor: Interferometric Synthetic Aperture Sonar.

Eric King (right) with Chief Engineer Dan Bühler in the shipyard office.

King oversees the operation of the ship, where it is going, and everything related to its operations. He also administers the science work and organizes the various expeditions while working within an international research vessel community “to find synergies between us and other institutions” so that they all can work on a much larger scale of ocean research and exploration.

How did King end up Senior Director of Operations for a state-of-the-art ocean research vessel? His remarkable journey, like many others, began at MMA.

When King graduated from Maine Maritime Academy with a BS in Maritime Transportation and Nautical Science, he set his sights waterward, taking a commission with the U.S. Coast Guard. He was posted to New York and then spent a few years in Cleveland. The Great Lakes were an “eye opener,” in particular the maritime side. He loved it.

While stationed on Lake Erie, King entered the marine salvage world, working with a New Jersey-based company. He resigned from the Coast Guard but kept a reserve commission. The next seven or so years he worked with offshore derricks and salvage tugs up and down the East Coast and in the Gulf of Mexico. From there, he went into general offshore and coastal harbor towing and some light marine construction and dredging. Each assignment brought new knowledge and adventures.

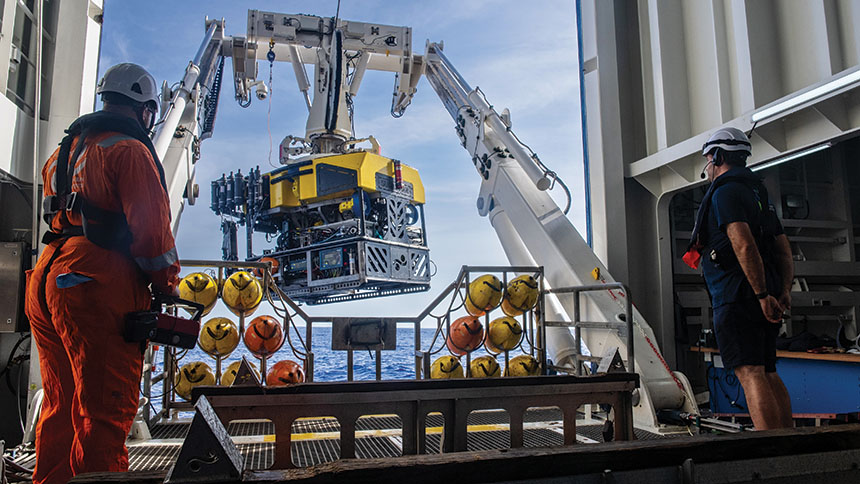

The remote operated vehicle SuBastian being brought on board the Falkor (too) from dive 491. SuBastian is used for scientific exploration of the deep sea and can reach depths of four and one-half kilometers.

At a marine salvage conference in Seattle one year, King fell in love with the Pacific Northwest. Yes, it was pouring rain, but in the nearby mountains there was more snow than he had ever seen. Reporting on his trip to his wife, Amanda, he vowed if there was ever a chance to relocate to Seattle, they would “throw the line off, pull chocks” and head west.

Sure enough, an opportunity to be port captain for the University of Washington’s oceanographic research ship opened up and King answered the call. He soon found himself at the helm of the R/V Thomas G. Thompson. The 274-foot vessel was named for Dr. Thomas Thompson (1888–1961), founder of University of Washington’s oceanographic laboratories and the first American chemist to focus on investigating the chemistry of seawater.

Once more, King entered a new field, ocean science, about which he knew little. Undaunted, he jumped feet first into his new role: supporting the ship with its cohort of mariners and working with scientists from all over the U.S. while crisscrossing the greater Pacific doing general ocean science work. He found it fascinating. He was hooked.

King doesn’t recall discussing ocean research vessels while at Maine Maritime Academy aside from some mention of the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration’s ships. While MMA’s Massachusetts counterpart has Woods Hole Oceanographic “right around the corner,” he notes, Maine Maritime was then somewhat removed from the world of ocean studies.

While commanding the Thompson, King gained experience working with various funders, including the National Science Foundation and the U.S. Navy Office of Naval Research. Making these connections would help in his next appointment.

Meanwhile, King attended the University of Washington graduate school at night. He remembers not seeing his family, his wife and two kids, a whole lot for three years while he pursued a master’s in public administration.

Shortly after earning the degree, King heard about a foundation in California that was converting a ship into an oceanographic research vessel. After a few interviews, he was brought on in 2010 as marine operations manager to help complete the conversion of a German fishery protection vessel into an ultramodern ocean research ship.

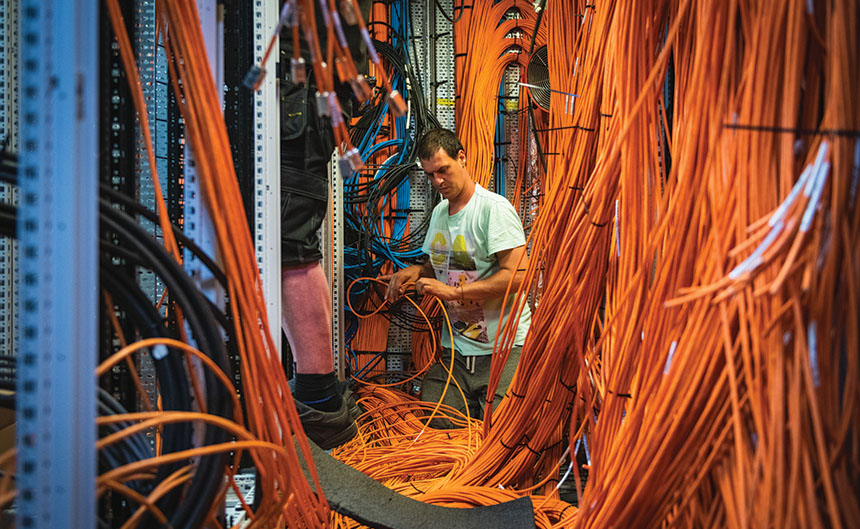

Some of the two hundred kilometers of fiber optic cable installed in the Falkor (too) to handle communication and data transmission.

Part of the conversion was the vessel’s name, which changed from Seefalke (Sea Falcon) to Falkor, the name of the luck dragon in the fantasy novel The NeverEnding Story. That was the easy part: major retrofitting was required to transform the ship into a world-class ocean research platform.

King spent the better part of two years at the Peters Schiffbau shipyard, a small operation in Wewelsfleth, Germany. At the same time, he visited other oceanographic institutions around the world lining up possible projects for the ship to undertake once it was fully outfitted. On these trips, he represented the Schmidt Family Foundation, launched in 2006 by Wendy and Eric Schmidt to address issues of sustainability and the responsible use of natural resources. More specifically, he was an ambassador for the Schmidt Ocean Institute, a 501(c)(3) organization dedicated to discoveries that benefit the health of the world’s oceans.

Fully operational in 2013, the 272-foot R/V Falkor began its cross-oceans explorations, mainly in the greater Pacific. In the South China Sea, they worked out of Vietnam and Indonesia. During the pandemic, they spent a year and a half circumnavigating Australia, mapping the Great Barrier Reef and sampling corals and sediments. For nearly a decade this repurposed ship with its corps of international sailors and scientists explored and discovered.

In March 2022 the Schmidt Ocean Institute announced the donation of the Falkor to the Italian National Research Council. Renamed Gaia Blu, the ship is now conducting science research in the Mediterranean.

The Schmidts wanted a vessel that would provide a larger base for research operations and be more capable of handling deep sea exploration. Rather than build something new, they once again acquired a vessel on the market, the Norwegian-designed MS Polar Queen built by the Freire Shipyard in Vigo, Spain, one of the busiest ports on the western coast of Europe.

King recalls the speed in which the transition was made. They finished up science research in the Pacific, traversed the Panama Canal and the Atlantic to deliver the Falkor to Italy, and then retrieved the Polar Queen from Norway and brought it to Vigo for refitting.

In April 2020 King assembled the shipyard owners and a team from the Schmidt Ocean Institute to figure out how they were going to convert what had been an offshore support vessel into an oceanographic research ship, which had been rechristened R/V Falkor (too). Between August 2020 and January 2022, they created, in King’s estimation, “one of the most capable research vessels in the world.”

King noted that much of the conversion was done in-house, without outside project management. “We oversaw what the shipyard was doing,” he notes, “but it was a design-build: design, construct, design, construct, design, construct.” Flexibility in contracts and funding allowed them to make steady progress in the rebuild. “The Schmidts wanted us out working with scientists, collecting data, doing exploration work,” King recalls.

Falkor (too) is specially equipped for deep sea exploration. It features one of the most comprehensive suites of sea floor and water column sensors. This equipment allows scientists to map the sea floor from just a few meters underneath the keel to the full ocean depth—nearly 11,000 meters of water.

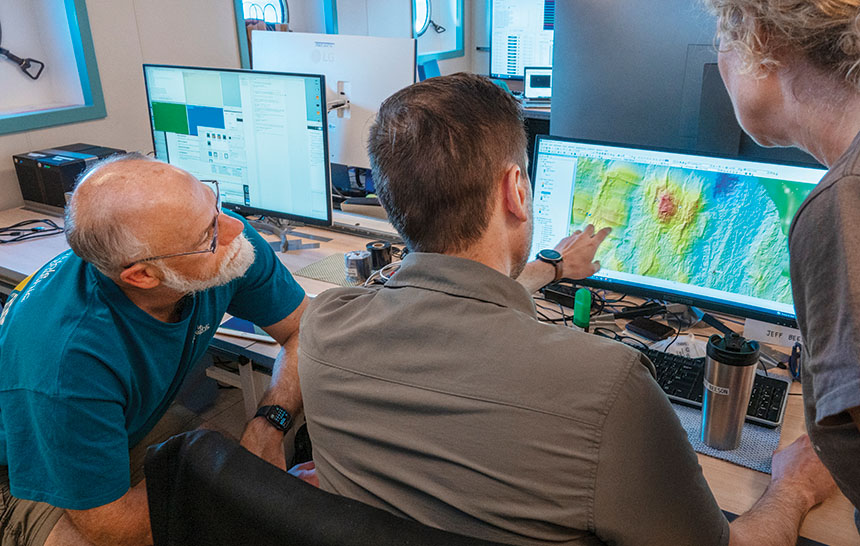

Scientists David Caress and Jeff Beeson look at a bathymetry rendering of an expedition’s destination.

Aside from pushing through ice in the Arctic, there is, says King, “pretty much nowhere we can’t go and do ocean studies.” You can hear the pride in his voice as he describes the ship’s capabilities, from its remotely operated vehicle launch and recovery system and its helicopter pad to its 150-ton offshore crane (the largest on any ocean science research vessel), its eight laboratories, six diesel generators, and two hundred kilometers of fiber optic cable coursing through the vessel to carry data and communications. The ship can be at sea for four months without refueling. With no home port, it’s underway 24/7, 365 days a year.

As for the crew, King smiles as he lists the countries from which hail the ship’s “international community of mariners.” Canada, Australia, South Africa, Bulgaria, Finland, Nigeria, the Philippines, Scotland, Hungary, Ireland—the range is global by design. The same goes for the cohort of scientists.

“Everybody is together,” King says, “and that’s huge.” Shared spaces and a shared mission create a “great bond” where scientists and crew members help each other. “The ship’s crew sits next to the scientists in the mess,” he relates, “and they’re able to talk about and ask questions and get some insight into why they’re doing the science so that the crew has a vested interest.” That camaraderie is key to the ship’s success.

Born in North Conway and brought up in Chatham, New Hampshire, at the edge of the White Mountains, King attended high school at Fryeburg Academy. He first became aware of MMA at a college fair in his high school’s gymnasium where he picked up a glossy tri-fold color brochure that featured photos of the T/S State of Maine. Those photos captured his imagination since his exposure to the ocean had “pretty much been limited to one offshore sailing adventure with family friends” and kayaking with his parents.

He has taken on these tasks “with MMA pride” and perseverance with the hope that future generations will benefit from his and his colleagues’ efforts

A tour with his grandparents of the MMA campus, the town of Castine, and the training ship “sealed the deal,” King relates. At the same time, he felt that being required to wear a uniform, get his head shaved, and do some cadence marching “would probably be the discipline and distraction” he was looking for at that time in his life. He remembers being awestruck by the sheer size and complexity of the ship “all the while being fascinated at how vessels of this magnitude could open up the world in ways unimaginable to me.”

Looking back, King considers his four years at MMA as “the foundation, the building blocks,” of a career that led him from the U.S. Coast Guard to commercial marine salvage and eventually ocean science. “What probably has remained with me most since the Field House graduation ceremony,” King writes, “has been the concept of ‘devotion to duty’ which was instilled in us MUGs from the moment we first walked up the ship’s gangway on day one of INDOC.”

King considers himself extraordinarily fortunate over the past nineteen years to be able to collaborate and partner with brilliant people from around the globe who are interested in applying the most advanced ocean-related technologies “to better understand the role the ocean can, and does, play in planetary and human health.”

Looking for new and innovative ways to help better understand the ocean and communicate its value “for the purpose of bringing about more than just awareness,” King admits, can be “a difficult and often uphill task.” He has taken on these tasks “with MMA pride” and perseverance with the hope that future generations will benefit from his and his colleagues’ efforts—and those of fellow MMA alums “who are also pushing hard within the ocean sciences to bring teams of scientists, researchers, and ocean engineers to the far corners of our open ocean.” █

Carl Little lives and writes on Mount Desert Island. He curated the exhibit “Clark Fitz-Gerald: Castine’s Celebrated Sculptor-in-Residence,” now in its second summer at the Castine Historical Society.

Several other Maine Maritime Academy graduates have been part of the crew of the Falkor and Falkor (too). They include:

- COLLEEN PETERS ’05 who sailed aboard Falkor as a marine technician in the ship’s Science Department before being promoted to lead technician and department head.

- DEBORAH SMITH ’02, also a marine technician in the Falkor’s science department and among the initial crew aboard Falkor (too).

- JULIANA DIEHL ’17, who joined Falkor (too) in the summer of 2022 while the ship was still undergoing conversion in Vigo, Spain. In 2015, Diehl, who was an MMA undergrad in marine science, sailed on the Falkor as one of the Institute’s first Students-of-Opportunity, and she was also an NOAA Hollings Scholar. She is currently a member of the ship’s Science Department.

Photos: Alex Ingle and Mónika Naranjo-Shepherd; All photos Courtesy of Schmidt Ocean Institute,

Post Comment

Comments are moderated and will be reviewed prior to posting online. Please be aware that when you submit a comment, you agree to the following rules:

Maine Maritime Academy reserves the right to delete any comment that does not comply with these guidelines and is not responsible or liable in any way for comments posted by its users. If you have a message for the editor, please email mariner@mma.edu.

Features

View All >Read More

Read More

Castine, Maine 04420All Rights Reserved © 2025

Privacy Policy & Terms

Web issue? Contact Webmaster