Somewhere out there in the GEO Belt, a vast region of outer space more than 24,000 miles from the Earth’s surface, six United States satellites are helping protect their mother country from the potential consequences of war. Significant credit and recent responsibility for this multi-billion-dollar array of technology goes to Marcus McInnis ’75.

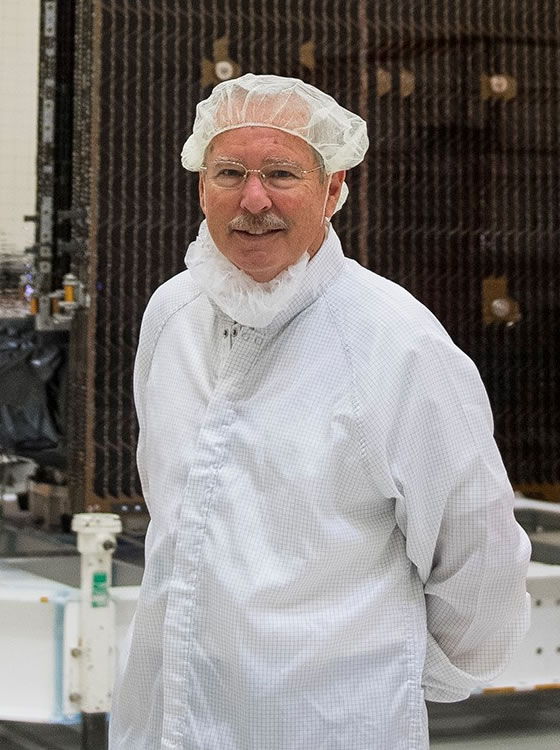

McInnis lives in the Los Angeles area and is the civilian Program Manager of the Space Acquisition Program for the US Space Force’s Space and Missile Systems Center.

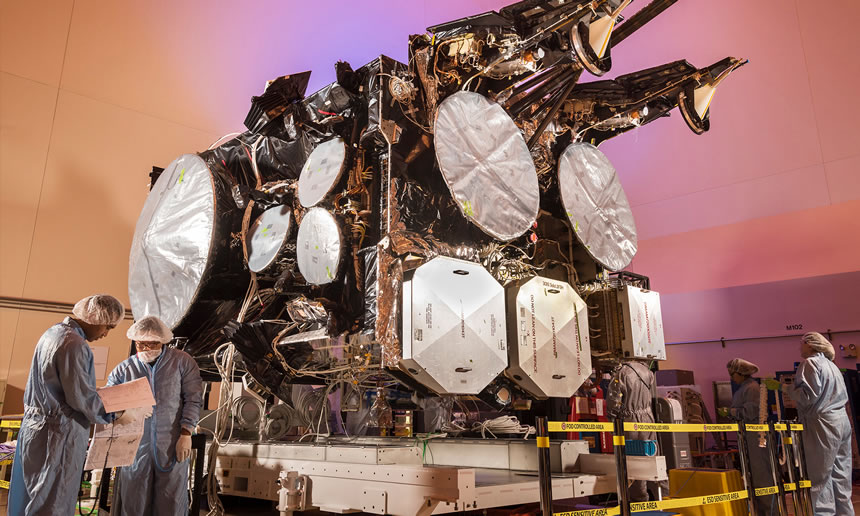

On March 26, 2020, McInnis and his team oversaw the launch from Cape Canaveral of the center’s sixth Advanced Extreme High Frequency satellite. In August, the team completed its testing of the satellite, which is among nine other military satellites that make up the AEHF MILSTAR Constellation for use in a critical defense communications system.

“One of the main capabilities of this satellite system is that we have assured communication in any scenario, any place on Earth, at any time,” McInnis said, “and that guarantees the effectiveness of our nuclear strategy.”

Even if nuclear war breaks out, McInnis explained, all key personnel, from the President of the United States to the Pentagon brass, and appropriate decision-makers in the field, can effectively communicate.

We have assured communication in any scenario, any place on Earth, at any time.

“The AEHF/Milstar Constellation provides global, survivable, protected, secure and jam-resistant communications for our warfighters, high-priority military ground, sea and air assets, as well as for key allies (UK, Canada, Netherlands, and Australia).”

“That’s a huge part of our national defense posture,” McInnis said. “Our system has 10 times the bandwidth of previous satellites. It is the principal communications method that supports the nuclear triad,” a group that includes the submarines, bombers (B-52s) and missile silos that are capable of launching nuclear weapons.

An Atlas 551 launches from the Cape with AEHF SV-6 aboard to start the five month orbit raising mission to reach the satellite’s geo-orbital slot 22,000 miles above Earth.

Although US defense spending on outer space projects has been controversial, Defense Department officials say the threat of unauthorized access of military messages and destruction of existing communications satellites is real, especially from China, and possibly from Russia. The Bush, Obama, and Trump administrations all have supported programs to defend US military communications assets in space, and Biden-appointed US Secretary of Defense Lloyd J. Austin III has promised to stay laser-focused on that objective.

The GEO Belt is the area in space where satellites can be placed in geosynchronous orbit. Today, there are more than 400 active satellites in the GEO Belt – including the ones used by satellite TV and internet subscribers. Once situated, these satellites rotate precisely with the Earth and appear stationary from the ground. That makes it easier for them to be used for communications, precluding the need to reposition satellite dishes and antennas.

Now, thanks in part to McInnis and his team, a new breed of GEO-belt satellites supports national security. But, although the concept of geostationary satellites had been around for nearly a decade when he graduated from high school, McInnis did not envision himself as a budding space wars expert.

The AEHF SV-6 gets its final check-out after completing both its environmental and Integrated Systems Test to ensure the payload is fully functional.

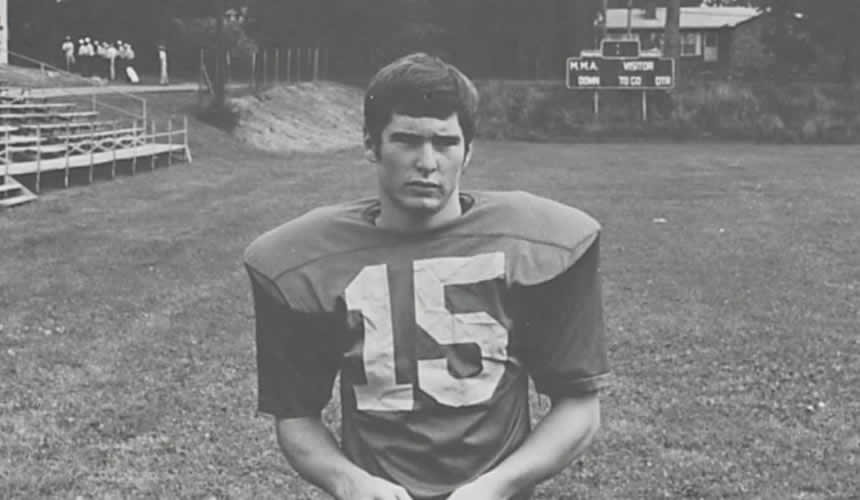

“I went to MMA because I wanted to play football,” McInnis said. The eldest of the nine children of Vincent Arthur McInnis and Jean Marie (Clemons) McInnis, he grew up in various small towns in Maine. His parents were educators, and his father moved the family from town to town as he gained better positions as a school principal, while his mother taught students how to use advanced business machines (including early computers).

McInnis played football for Wilton Academy and Blue Hill High School in nearby Farmington. While neither of these Maine communities was far from the sea, life as a Merchant Marine or Naval officer was not McInnis’s prime mover. Once he enrolled at MMA as an engineering student and joined the school’s football team, however, McInnis began to appreciate the qualities that he believes are still the school’s greatest assets.

“We spent four years studying to take one test [the Merchant Marine certification],” said McInnis, “but what you learned along the way was the key – discipline, teamwork, approaches to problem-solving and critical thinking in operational settings… well, you couldn’t get that in a regular college.”

During McInnis’ second year at MMA (’72-’73), the academy joined the NCAA Division III New England Football Conference and won the conference championship that same year. Records credit McInnis, a defensive back, with two pass interceptions that year.

McInnis played four seasons for a winning Mariner football team. “Proof,” he said, “that we were young once and RC’s play sports.”

McInnis credits Athletic Director Verge Forbes, who later became academic dean at MMA, and defensive backfield coach Len Tyler, later, MMA president, for being his greatest influencers.

He became class president and student council VP before becoming Regimental Commander his senior year. McInnis was subsequently interviewed by Adm. Hyman G. Rickover and offered a position on his staff. McInnis was interested in Rickover’s nuclear power program as a way to augment his steam and diesel power plant qualifications with experience in naval nuclear power. At the time, several shipping companies were considering bringing nuclear powered ships (back) into the commercial fleet. But practical and political issues prevented large scale adoption of nuclear power for commercial shipping. McInnis shifted his attentions to naval aviation, attending flight school in 1976 with Rickover’s support.

McInnis’ naval fleet career was in EA-6B Prowlers, the electronic warfare – medium attack, carrier based aircraft. He completed five deployments aboard various air craft carriers. His successful naval career lead to being selected for the Naval Test Pilot School (class ’88) and a subsequent position as the head of the Electronic Warfare and Reconnaissance division at the Naval Test Center at Patuxent River, Maryland where he logged time in 16 different aircraft.

What I learned at MMA – discipline, teamwork, approaches to problem-solving, and critical thinking … well, you couldn’t get that in a regular college.

The Navy recommended McInnis as an Astronaut candidate in 1987 where he was a semi-finalist in NASA’s group 12 selection. He attended the Naval Postgraduate School (Aerospace Engineering); National Defense University (National Security Affairs) and the George Washington University (MPA). He finished his career working for the Defense Intelligence Agency as the Chief of All-Source Collection and principle representative to congressional committees for technical issues.

After the Navy, McInnis worked 15 years for the Lockheed Martin Corporation running several defense programs and retired as the operations director of the national Cyber Security Innovation Center and the Director of Shaping Research in 2012. He worked as a business consultant in Africa and the Middle East before moving to California to support the Space and Missiles Systems Center in 2017. He recently finished his position as the Program Manager for the highly successful AEHF Program (launching SV-4, 5 and 6) and is transitioning to be the Chief of the Test and Evaluation Branch for the Space Production Corps’ $16 billion portfolio of space vehicles.

McInnis’s success came as no surprise for his classmate Gary Dustin. A retired Merchant Marine who met McInnis in engineering class when they were freshmen, Dustin attributes McInnis’s accomplishments to his eagerness to accept new challenges. “Without something to challenge him, he’d be bored,” Dustin said. “He was also influenced by his parents, as educators. He was like a teacher in our class. He helped everybody, and not just me. He had a very inquisitive mind, always interested in what you had to say. He really listened.”

Dustin claims comfort from knowing McInnis plays a key role in national security. “It’s easier to sleep at night knowing people like Marcus are protecting us.”█

Hot Flight in Cold Sky

Ever since Brigadier General Chuck Yeager was profiled in The Right Stuff, test pilots have been held in awe and frequently asked to share war stories. Marcus McInnis is no exception. Here he relates an attempt to attend an MMA class reunion in the 1980s:

While serving in the Air Force, a classmate and I were always looking for extra flight time. We got permission to do a cross-country flight over the weekend, checked out a jet, and found ourselves headed to Maine [from Maryland’s Naval Air Station Patuxent River] at 40,000 feet. As things sometimes go in military jets, they went from good to bad to worse. We found ourselves in an imbedded thunderstorm, in icing conditions without power or most of our instruments.

Telling right-side up became difficult, and keeping it [upright] was a challenge. The ride was brutal. Thunderstorms are not pleasant places. We couldn’t see out, as the cockpit was totally frozen over. We lost communications, then more electrical systems, then the right engine (luckily, we had a left), and began coming downhill as the wings loaded with ice.

We anticipated that if we could keep it flying somewhat it would thaw out as we got lower. We would get better control, the antennas to the radio would start working so we could declare an emergency, and we would be able to find a place to land, as long as the big sky theory worked. The trick, of course, is that all [of this] had to happen before the ground reached up and smacked us.

Obviously, things did work out. We (very skillfully) found ourselves on descent to an airfield in Plattsburgh, New York, after an incredible and very busy 30-minute flight back to the Earth that seemed to be only an instant. And the very skillful part has become more skillful in the retelling over the years. We unfortunately never made it to the reunion. But as luck would have it, it took a few days to fix the jet, and Plattsburgh turned out to be quite the college town!

Photos: Courtesy of Marcus McInnis

Post Comment

Comments are moderated and will be reviewed prior to posting online. Please be aware that when you submit a comment, you agree to the following rules:

Maine Maritime Academy reserves the right to delete any comment that does not comply with these guidelines and is not responsible or liable in any way for comments posted by its users. If you have a message for the editor, please email mariner@mma.edu.

Features

View All >Read More

Read More

Castine, Maine 04420All Rights Reserved © 2026

Privacy Policy & Terms

Web issue? Contact Webmaster