There are quite a few ships around the world that are over 100 years old. In fact, there are quite a few that are centuries old. I’ve viewed the Gokstad ship, 1,200 years old, in a museum building in Oslo. I’ve toured the Vasa, launched in 1628, in her drydock building in Stockholm. I saw the USS Constitution, launched in 1797, under sail once. But I can’t think of another 100-year-old sailing ship that is still sailing regularly, and still doing what it was originally built to do, except for Bowdoin, which turned 100 on April 9 of this year.

As Captain Elliot Rappaport once said of Bowdoin, “There’s a big difference between a ship that went to the Arctic and one that goes to the Arctic.”

Donald (“Mac”) MacMillan was bitten by the Arctic bug when he served with Peary on Peary’s 1909 North Pole Expedition. Peary claimed to have seen a large landmass in the polar sea, which he named Crocker Land. MacMillan was determined to go back and find it. That expedition, which departed in 1913, was intended to last no more than two years, but he ended up staying for four, when two successive relief ships failed to reach him. It was during that long spell that he decided what a proper expedition required, and that was a good ship.

When I was in that ice barrel, I could feel Mac’s presence beside me— ‘Relax,’ he said, ‘and she’ll take care of you.’

Mac considered the failings of other ships that had been beset in or crushed by ice, left without fuel, or damaged by grounding, and came up with a list of requirements for a purpose-built expedition vessel. She would be as small as he could get away with, which would allow for maneuvering in tight spots. She would have a hull with rounded sides to prevent the ice getting a grip on her. With a wineglass shape, she should “pop” out of the ice if it tried to grab her. She would carry her greatest beam well aft, which would shunt the ice bits away from the propeller. She would have a draft of about ten feet, matching the height of tide on the Greenland coast, which would allow her to be beached at high tide for repairs. She would have a simple engine that could burn anything from diesel to kerosene to whale or seal oil. She would be as strong as a shipyard could make her, but, just in case, there would be two watertight bulkheads so that if “I broke her stern off, she would float, and if damaged for’ard, she would still float, and if she broke in half, both ends would float.”

Bowdoin passing a large, tabular iceberg in Disko Bay, Greenland on the 1991 voyage.

After the Crocker Land expedition, and a three-year stint in the Navy, Mac commissioned William Hand, a notable yacht and workboat designer, to design his ideal vessel. He chose Hodgdon Brothers Shipyard in East Boothbay, Maine, to build her.

The construction estimate was $35,000, of which Mac had less than $3,000 on hand. But he promised to pay the yard somehow, and they started work with a handshake. He ended up selling shares to enthusiastic supporters for $100 apiece, and Bowdoin was built. Launching day was April 9, 1921.

The maiden voyage was to the west coast of Baffin Island, a region that had yet to be explored by anyone but the Inuit. On the way there, in a moment of confusion at the helm, Bowdoin ran headlong into an iceberg. The impact was enough to sink practically any ship of any size, but Bowdoin suffered almost no damage.

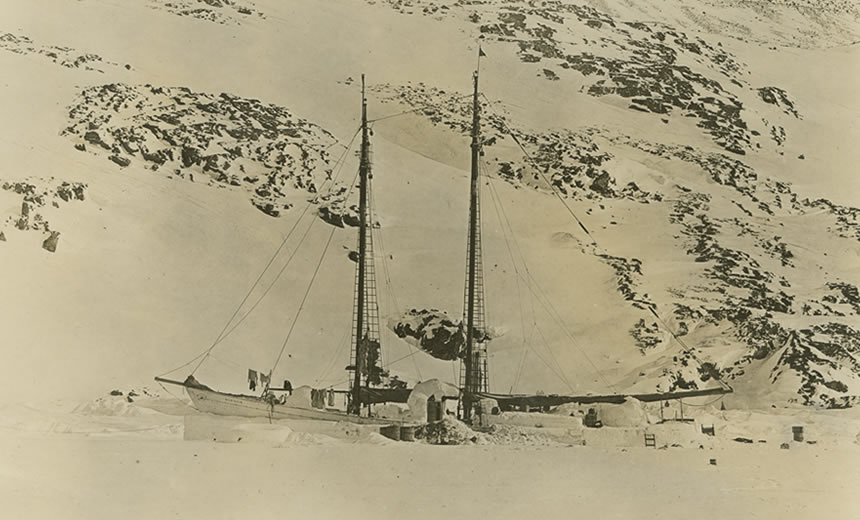

MacMillan found an ideal harbor, uncharted, but well protected from ice pressure by virtue of a very narrow opening, and he named it Schooner Harbor. (He reserved the name Bowdoin Harbor for a different berth in northern Labrador.) There they moored the schooner and prepared the ship and crew for long winter nights. Once frozen in, with the help of local Inuit, the crew built a snow wall around the hull and igloos over the hatches, making her snug and relatively comfortable for the ten-month stay.

For his next voyage, Mac planned a multi-year expedition to far northern Greenland, stomping grounds from his Crocker Land expedition. Again he found a suitable place, Refuge Harbor, where he settled the vessel in as before, this time for eleven months.

He very nearly didn’t make it out.

Design: William Hand

Sail Area: 3,000 square feet

Launched: 1921, Hodgdon

Brothers Shipyard, East

Boothbay, Maine

Auxiliary Power: Cummins 855, 190 horse power auxiliary – 7 knots, maximum

Hull: White Oak

Rig: Grand Banks knockabout schooner

Deck: White Pine

Masts: Douglas fir

Sails: Oceanus©

Overall Length: 88 feet

Crew: 16

Beam: 21 feet

Speed: 10 knots maximum

Displacement: 66 tons

Draft: 9.5 feet

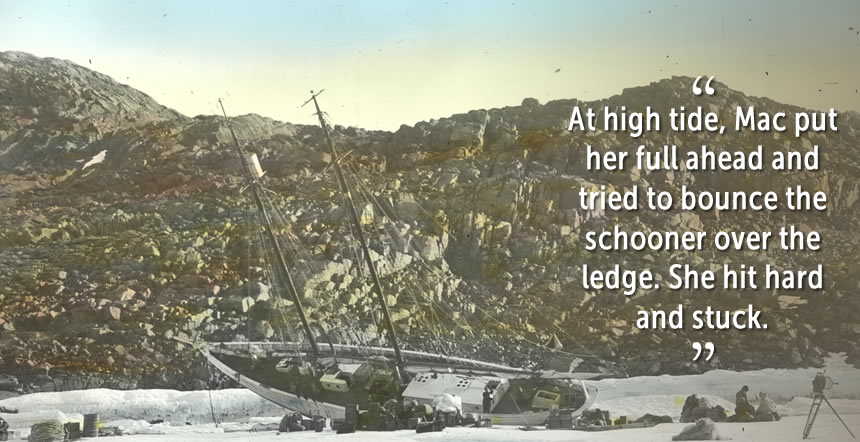

By the end of July 1924, it looked like the ice would not leave the harbor that summer. A narrow and shallow shore lead was all that had opened up, with just a little less depth than Mac needed to get out. He determined that it was worth a try, or otherwise Bowdoin would probably be stuck for another year.

At high tide, Mac put her full ahead and tried to bounce the schooner over the ledge. She hit it hard, and stuck. With the tide dropping, the crew feared the schooner would lay over and fill as the next tide rose, so they rigged tackles to the shore to hold her upright. That worked, until it didn’t. The lines parted; the schooner fell hard and cracked a couple of planks. Working feverishly, they unloaded all the gear they could, to lighten the vessel, and in case they needed to camp ashore for the winter. But Bowdoin did float on the next tide, and was able to get over the hump.

She would have made a clean getaway, had not an iceberg drifted into and run aground in the only entrance (or exit) of the harbor. Mac surmised that if he hit it hard enough, perhaps the schooner could break through and get out. Bowdoin backed up and then rammed the solid ice at full speed. She stopped dead, but indeed a crack in the ice appeared, and as the vessel pressed against it at full throttle, it gradually opened, and she slipped through.

President Ken Curtis ’52 saw the ship as a link to maritime history, a platform for teaching seamanship—and for fundraising.

Bowdoin had now proven herself, and proven MacMillan’s theory of what an ideal Arctic expedition vessel could be. For 33 years she spent few summers away from the Arctic. Her missions were for training and education for the mostly college-aged, young people.

During World War II, the vessel was purchased and commissioned by the US Navy and sent back up to Greenland to conduct surveys of sites for US airbases. The work earned her place in US naval history and two WWII service ribbons.

After the war, she was offered back to MacMillan, who bought the disheveled, stripped-down hulk for $4,000. At 71 years old, Mac had plenty of energy left. With help, he restored her to sailing condition. He stretched his resources to buy a new Cummins diesel engine, and when the invoice arrived, it came with a letter of support from the head of the company and was marked “Paid in Full.” The relationship with Cummins has endured to the present day.

Mac and Bowdoin continued voyaging to Newfoundland, Labrador, and Greenland almost every year until 1954 when he turned 80 and finally retired.

He donated the vessel to Mystic Seaport in Connecticut, where she was to become a museum piece. But Mystic didn’t have the resources to maintain her, and after nine years of neglect, she was almost too far gone to save.

Bowdoin hard aground in Refuge Harbor, trying to depart. She was refloated on the next high tide.

In 1968, Capt. Jim Sharp of Camden, Maine, approached Mac with a proposal to restore the ship to sailing condition. Mac was delighted, and Jim spent the next year rebuilding her. Several friends helped, and one young helper, John Nugent, would stay with Bowdoin for many years.

As all hands knew that Mac was in declining health, they worked extra hard to get the job done. In the fall of 1969, Jim and friends got Bowdoin underway and sailed her down to Provincetown, Massachusetts, where Mac saw his proud ship under sail once again. He died less than a year later.

There followed a period of about 10 years when Bowdoin was commissioned as a private yacht, a charter vessel, and a school ship for kids. Eventually new safety rules meant the vessel would have to be rebuilt in order to continue paying her way.

A fundraising campaign was launched, and from 1979 to 1984 she underwent a rebuild so complete that she received a US Coast Guard certificate as both a passenger and a sailing school vessel. The lion’s share of this work was done by John Nugent, often working alone.

When Cummins learned that Bowdoin’s engine needed work, the company traded it for a brand new one, realizing that she had the first marinized engine they had built, and one of their oldest engines still in operation. That engine is now on display in the lobby of the Cummins headquarters in Indiana.

The rebuilt schooner ended up with the Hurricane Island Outward Bound School. But after a couple of years, that organization determined the vessel wasn’t a good fit for their mission, and word got out Bowdoin was again looking for a home.

At that time, Chris Kluck was a student at Maine Maritime Academy, and he had a passion for sailing. I was an ex-schooner captain with a new job on the faculty. Kluck got wind of Bowdoin’s situation and suggested we try to bring her to MMA. I was too new to my job to spare much effort, but promised to support him. Soon thereafter, someone pulled a fire alarm in the dorm and Kluck had the foresight to bring and circulate a petition, asking students mustering in the courtyard to support acquiring the vessel for a sail training program.

President Ken Curtis ’52 was impressed by the initiative and also by the opportunity. He saw the ship as an iconic link to Maine’s maritime history and as a platform for teaching seamanship. He also saw her as a platform for fundraising, and he was starting MMA’s first major capital campaign.

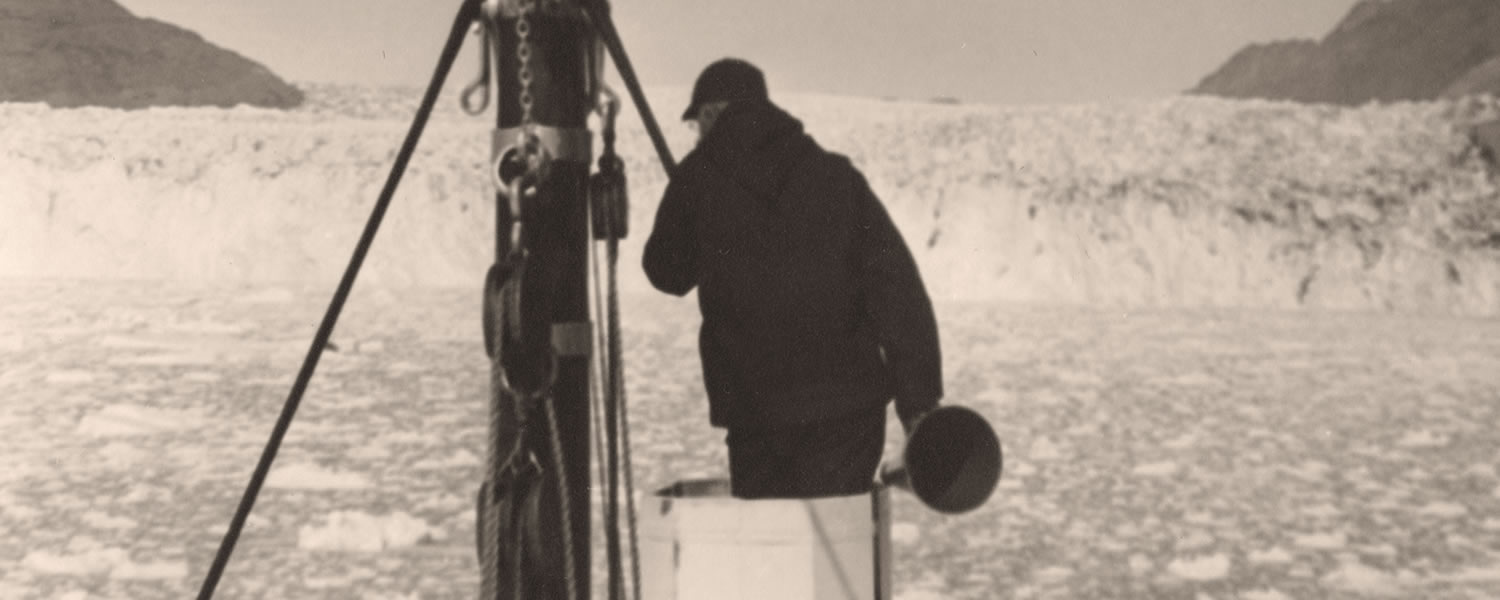

Winter quarters, Refuge Harbor, 1923-24.

MMA acquired Bowdoin in the fall of 1988, and I got the job as captain. In our first season together, we sailed the Maine coast with students aboard, as what I liked to call “modern day pirates.” We’d sail into a port, host a fundraiser, and sail away with everyone’s money. Curtis liked to say that capital campaign was largely funded across the decks of Bowdoin.

At the end of the 1989 season, I proposed taking the vessel back to Labrador. To my surprise, Curtis said, “Go for it.” And so we did.

Our six-week voyage to Nain, Labrador, in July and August of 1990, was a reunion for Bowdoin. At every port in Nova Scotia, Newfoundland, and Labrador, people were astounded to see the ship again. She was a legend there, even more so than in Maine. It had been 36 years since they had seen her. They showed us photos of themselves as children on board with Mac. Two Inuit elders in Nain insisted on presenting me with chocolates, returning the favor that Mac had done for them when they were little. We visited the schoolhouse that Mac had built for them with materials delivered on Bowdoin.

That trip was so successful that on our return I suggested to Curtis that we shoot for Greenland and the Arctic Circle the following season. Again, he said yes.

The 1991 voyage lasted nine weeks and covered 5,000 miles, crossing the Arctic Circle and reaching 70° north latitude. Again the locals were thrilled to see their beloved “White Ship.” We were able to find photos of some of them in the old copies of National Geographic that we had on board, some dating back as far as 1923.

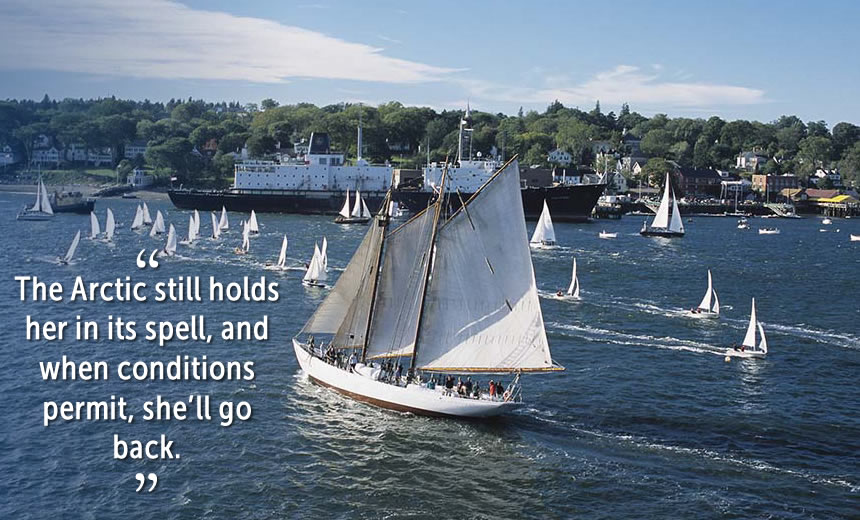

Since the Arctic voyage, Bowdoin has continued Mac’s legacy of taking people north to Nova Scotia, Newfoundland, Labrador, and Greenland. Bowdoin has voyaged north of the Arctic Circle under the MMA flag three times.

In 2015, 30 years had passed since her last rebuild, and it was time for Bowdoin to get another makeover. A $1.5 million capital campaign was initiated, and the first phase was a rebuild at Wayfarer Marine in Camden that included replacing the deck and upgrading many of her systems and engine. The Cummins company sent a technician to Castine to supervise MMA students in the Small Craft Technology Lab in rebuilding the engine, and provided all necessary parts. Phase II of the rebuild, completed at Bristol Marine in Boothbay Harbor over the winter of 2018-19, involved replacing planking and frames as necessary below the waterline.

MMA’s entire small vessel fleet underway for the “Sail MMA Day,” on June 6, 2011.

Throughout the rebuild, pains were taken to keep her as historically accurate as possible. She is still the vessel Mac specified: strong enough for ice work, with watertight bulkheads, a short rig, and an ice barrel aloft for the captain to stand in while conning her through the ice.

I can assure you when I was in that barrel picking my way through the ice, I could feel Mac’s presence beside me. He seemed pleased. He kept telling me, “Relax, she’ll take care of you.”

By the summer of 2019, she was once more in like-new condition, and planning began to celebrate her 100th season with another Arctic voyage.

Unfortunately, the coronavirus pandemic put that plan on hold. Even so, shortly after her birthday on April 9, Bowdoin will get underway once again for a season doing exactly what she was built for — scientific research, cultural study, and exploration while teaching seamanship and providing adventure for the young people (mostly MMA students) who are fortunate enough to earn spots as crew.

The Arctic still holds her in its spell, and when conditions permit, she’ll go back.█

The Future of Bowdoin

How a wooden vessel can live forever.

Piece by piece, it can be rebuilt indefinitely, maintaining at least the soul, if not many of the pieces, of the original vessel. Those periodic rebuilds must be anticipated.

President Brennan realized the importance of maintaining Bowdoin and planning for her financial future. He formed the Schooner Bowdoin Future Committee consisting of current and past Bowdoin captains, the Vice President for Advancement, IBL faculty, and other stakeholders. The goal was to develop a plan to cover the next rebuild projected to take place by 2045.

The rebuild plan, developed and approved in the fall of 2019, is a three-pronged approach combining funds raised through an annual appeal, interest earned through the Bowdoin’s existing maintenance endowment, and monies from the Yacht Donation Program.

With this plan now in place, MMA can cover any major repair while providing the necessary funding for her next rebuild in 2045.

Alumni, parents, friends, and citizens of the State of Maine can be proud that Maine Maritime Academy has not simply maintained this historic vessel for our own use, but will also be leaving her in good hands for all to enjoy for another half a century.

Photos: courtesy of The Peary-MacMillan Arctic Museum, Bowdoin College, Tom Stewart, Ben Magro, Billy R. Sims; Sail plan courtesy of Peter S. Zimmerman

Post Comment

Comments are moderated and will be reviewed prior to posting online. Please be aware that when you submit a comment, you agree to the following rules:

Maine Maritime Academy reserves the right to delete any comment that does not comply with these guidelines and is not responsible or liable in any way for comments posted by its users. If you have a message for the editor, please email mariner@mma.edu.

Features

View All >Read More

Read More

Castine, Maine 04420All Rights Reserved © 2026

Privacy Policy & Terms

Web issue? Contact Webmaster